10. Enslaved and Hired Farm Labor

What’s growing here? Potatoes

Farmers often could not cover their labor needs with family members alone, turning to different forms of hired and enslaved labor throughout history. Most New Jersey farmers, by the mid-nineteenth century, did not own enslaved farm laborers, so when farmers needed extra hands for a big harvest, they would often “borrow” enslaved laborers from neighbors, and would pay their owner for the hours the enslaved person worked.

Later, hired farm hands worked alongside farm owners in the fields, often living on the farm in tenant housing. The farmhouse near this garden started as a small house for farmhands, who worked on the adjacent Clarke farm, before a large addition converted the house into a grand family home.

Day laborers played an essential role as well. Digging up potatoes, a major crop on Princeton farms, was labor intensive work. Frank Updike, a relative of the family that owned this farm, recalls that, during the potato season, entire families would hire themselves out. These workers were often paid meager wages. A Princeton farmer recalls paying his hired hands $15 per week in the 1930s, which would today be a salary of just under $12,000 per year.

Today, farm labor and wages remain a difficult issue. The challenging economics of agricultural businesses often compete with the desire to fairly compensate workers. After much debate, in 2019, New Jersey passed minimum wage increases for farm workers that, though lower than other industries, would make the state’s farm workers the highest paid in the Northeast by 2024.

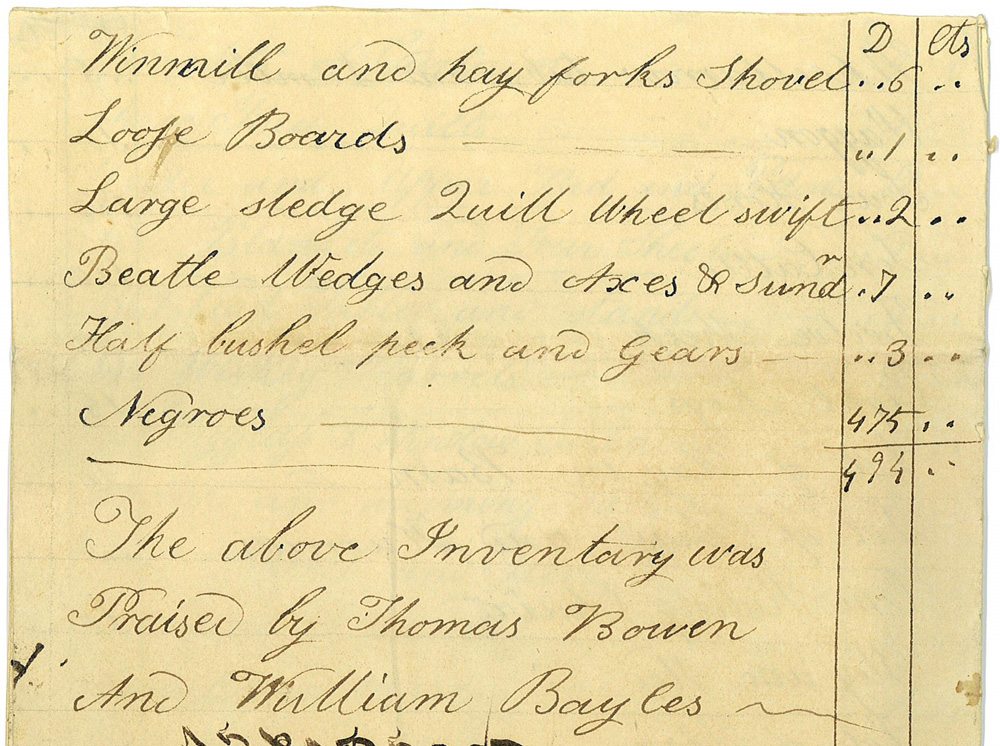

Richard Lake owned what he called a “Homestead Farm” on unincorporated land just north of Princeton. Upon his death in 1822, an inventory of his household and farm listed “Negroes,” valued at $475.00, alongside agricultural tools.

Lake Family Papers. Historical Society of Princeton