One hundred years ago, on August 26, 1920, the 19th amendment to the United States Constitution was certified, officially making it constitutional for women in the U.S. to vote. In practice, this right did not initially extend to all women — Native American women, Chinese immigrant women, and Southern Black women remained disenfranchised until 1924, 1952, and 1965, respectively.

Still, the victory in 1920 remains a major milestone, a long and hard-fought win in an ongoing struggle for women’s rights, voting rights, and civil rights. But its passage was never certain, especially in Princeton, a town that embodied the difficulties in bringing communities, and families, to consensus on the issue of a woman’s right to vote. Though many towns experienced this division, the nation closely watched Princeton, then home to the sitting President and a former First Lady.

The fight to grant women the vote showed that the expansion of freedoms in the United States is never inevitable. Major grassroots efforts of millions of ordinary individuals nationwide fought for, and against, the cause.

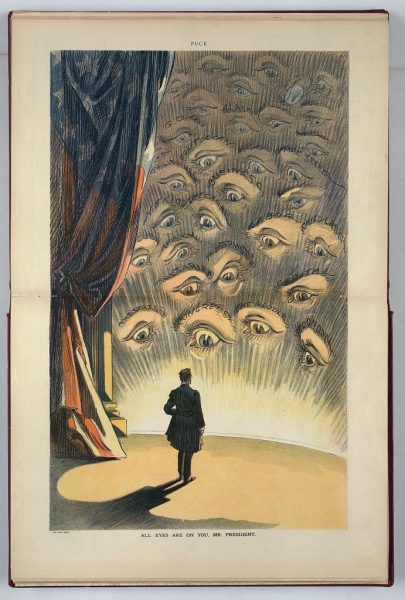

All Eyes on Princeton

It is fall 1915. The women’s suffrage battle has already become one of the longest fights for democratic and civil rights in the nation’s history. At this time, the leaders of the suffrage movement are focused less on the federal amendment to the United States Constitution, and more on convincing individual states to amend their own state constitutions to allow women to vote.

New Jersey is to lead off a series of women’s suffrage referendum elections in four eastern states that are the most antagonistic to women’s suffrage. Suffragists view these states, the most populous in the nation, as a major juncture in their state-by-state battle for voting rights, and as a critical measure of public sentiment on the matter.

All eyes are on President Woodrow Wilson – who has avoided the contentious suffrage question up to this point – as he travels to his home polling place in Princeton to cast his own vote in the New Jersey referendum. All eyes are on Princeton.

The Battle Begins

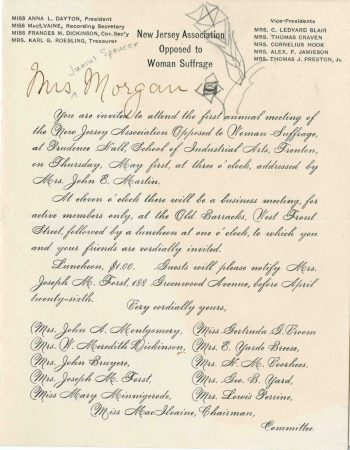

In the lead up to the 1915 referendum vote, the town of Princeton, at best ambivalent to women’s suffrage until that year, became a locus for deep engagement with the suffrage question. In the spring of 1915, several townspeople formed the Princeton Suffrage Committee, as a foil to the Princeton Branch of the New Jersey Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage, which had formed a year earlier.

Both organizations spearheaded aggressive campaigns to educate male voters. Both sides held mass meetings in Alexander Hall on the Princeton University campus, hosting speakers of national and international importance on the suffrage question, including Rev. Dr. Anna Howard Shaw, president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, and Minnie Bronson, general secretary of the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage. Both suffragists and anti-suffragists penned letters to the editor in local, regional, and national publications, signing with their Princeton addresses. Anti-suffragists hosted fundraising balls. Suffragists canvassed door-to-door and shouted speeches in the street.

Princeton’s Anti-Suffragists

The anti-suffrage cause was the earliest and the most dominant view to take hold in Princeton, which was home to anti-suffrage heavyweights.

Frances Folsom Cleveland Preston, a Princeton resident since 1897 and the remarried widow of former President Grover Cleveland, was one of the most high profile women of her day. She offered deeply influential support for the anti-suffrage cause, lecturing in Alexander Hall. She was the Vice President of the New Jersey Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage when it formed in 1912, serving in that role until the passage of the 19th Amendment, and was the founding President of the Princeton Branch when it was formed in 1914. News outlets nationwide covered her appointment to these positions.

Colonel William Libbey, a Princeton University Professor of Physical Geography, was the founding president of the New Jersey Men’s Anti-Suffrage League, formed in 1914. His wife, Mary Elizabeth Green Libbey, was a member of women’s anti-suffrage groups.

Other prominent local anti-suffragists included Princeton University deans Henry B. Fine and William Francis Magie, as well as Magie’s sister Henrietta Oakley Magie.

Princeton’s Suffragists

Pro-suffrage sentiment had, up to this point, not gained much traction in Princeton. But with the referendum looming, a group of supporters started to officially organize as the Princeton Suffrage Committee.

Pro-suffrage sentiment had, up to this point, not gained much traction in Princeton. But with the referendum looming, a group of supporters started to officially organize as the Princeton Suffrage Committee.

Catherine Warren (pictured here outside her home at 133 Library Place) was treasurer of the New Jersey branch of the Congressional Union, a more radical arm of the suffrage movement, as well as the President of the New Jersey State Federation of Women’s Clubs.

Jean Guerney Fine Spahr was the Chairman of the Princeton Suffrage Committee and represented Princeton at statewide suffrage meetings. Her sister, May Fine, also a member of the Princeton Suffrage Committee, was the college-educated headmistress of Miss Fine’s School– today Princeton Day School. Their brother was anti-suffragist Henry B. Fine.

Eleanor Beach was the wife of the minister of the First Presbyterian Church and mother of Sylvia Beach, another suffragist and the founder of the famed Shakespeare and Company bookstore and lending library in Paris.

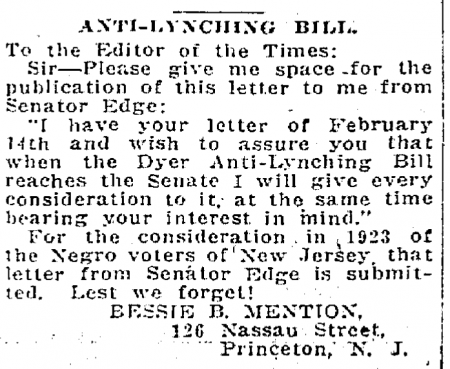

Bessie Brown Mention, a black suffragist in Princeton, would later become instrumental in organizing New Jersey’s black women in Republic Party politics.

Jesse Lynch Williams, Princeton University psychology professor and first winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Drama, became a very public supporter of suffrage, penning a national pamphlet, “A Common-Sense View of Woman Suffrage.”

Williams had a humorous, sarcastic approach to his arguments. In response to a New York Times anti-suffrage editorial, he wrote, “From the able way in which the news of the world is covered in THE TIMES I should say that your newspaper was well named. After reading ‘The Woman Suffrage Crisis’ on the editorial page one is tempted to ask, ‘What times?– does the writer know what century he is living in?’”

Key Arguments

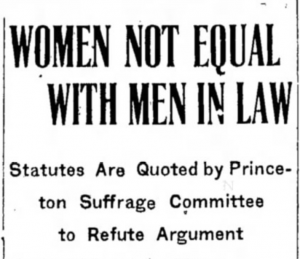

Princeton’s suffragists pointed out the many ways in which women were not equal to men under the law. They argued that, among other injustices, women’s suffrage could remedy the fact that women were denied the right to inherit property, married women could not independently own property, and after divorce could not have custody of their children. Moreover, they argued that women paid taxes, were an increasing presence in the workforce, and deserved by democratic right to be represented in their governments.

Princeton’s anti-suffragists espoused the “separate spheres” argument — in the natural order, women and men had different capabilities and belonged in different domestic and public spheres. They also argued that women did not want or need the vote because their husbands represented them at the ballot box. On the question of necessity, in Princeton, as nationally, anti-suffragist women advanced social reform issues through their personal connections with politicians. To them, this “indirect influence” was a more respectable, non-partisan means to an end for women, but suffragists argued it was an avenue for action that was open to a privileged few.

On Campus Opinions

The campaign by Princeton’s suffrage organizations was directed at Princeton students as much as townspeople, with the campus newspaper, the Daily Princetonian, reporting on all pro- and anti-suffrage campaign activities.

At first, it seemed Princeton University — which the Daily Princetonian editor called “the synonym for conservatism” during the referendum campaign — would align itself squarely with the anti-suffragists. Students and alumni appeared to encourage the popular stereotype of suffragists as masculine and misguided by portraying their movement as a joke. In 1910, the all-male Class of 1900 satirically dressed as suffragists in long white dresses, holding “Votes for Women” signs, to march in the annual “P-Rade” during class reunions.

However, by the fall of 1915, the feeling toward suffrage on campus had changed. University President John Grier Hibben announced that he would vote in favor of woman suffrage in the upcoming referendum, and a poll showed that 56% of faculty members would do the same. The Daily Princetonian published an editorial supporting woman suffrage on October 15, 1915. In the referendum election, the two voting districts in which Princeton University students lived came out in favor of woman suffrage, the only districts in Princeton to do so.

Photo Caption: The Princeton University Class of 1900 dressed as suffragists in the 1910 P-Rade on Nassau Street.

A Devastating Defeat

Just under two weeks before the special election, President Wilson announced he would support woman suffrage in the New Jersey referendum. In his highly anticipated statement, he clarified that this was his “private conviction as a citizen of New Jersey” and that he remained opposed to the federal amendment, holding fast to his belief that suffrage was a matter that “should be settled by the states.” Nevertheless, suffragists viewed this as a tremendous victory that would surely guarantee the referendum’s passage. Anti-suffragists meanwhile argued that it was too little too late. With “both sides claim[ing] victory,” according to the Associated Press, the actual outcome was anything but certain.

In the end, with voter turnout unexpectedly high, the referendum was defeated in New Jersey by approximately 50,000 votes, a 16% margin. In Princeton, the referendum lost by 14%. The vote in Princeton, and Wilson’s own ballot, garnered immense curiosity and was reported in great detail across the nation, as far away as Alaska.

Search for a Scapegoat

Despite Wilson’s support for the pro-suffrage side, the “antis” had carried his home district, town, and state. Suffragists and journalists the next day searched for a reason why. They blamed black voters for the defeat, suggesting that they were not informed and were easily swayed by private interests. Articles cited as evidence the “heavy negro vote” in several lost Princeton districts, including Wilson’s.

Prominent black citizens of Princeton and Trenton challenged this claim. In letters to the editor, they argued that “the negro studied the woman suffrage question as did other men” and pointed out that the 50,000-vote margin was greater than the total number of black voters in the state. The authors shared information about black voters they knew were in favor of suffrage, including “one of the largest colored property owners in Princeton and leading man among his race” who “openly for weeks before the election advocated woman suffrage.”

“Scapegoating” black voters, as one writer called it at the time, revealed the racism embedded in the suffrage movement. Though the mainstream suffrage organizations sidelined them, black suffragists, and many black voters, recognized that black women’s suffrage was a critical tool in their fight for racial justice.

The Movement Resets and Recedes

The defeat of the referendum in New Jersey was followed by resounding defeats that fall in Pennsylvania, New York, and Massachusetts. It was a turning point in the national movement. The national leaders finally abandoned the state-by-state approach they had prioritized for decades, setting their sights instead on the federal amendment. This shifted the movement’s center of gravity away from small-town suffrage organizations and towards Washington, D.C.

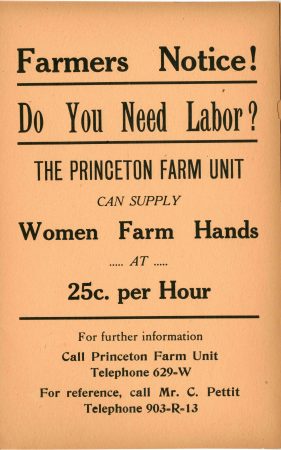

Then, when the United States entered World War I in 1917, the hundreds of local women who had mobilized for and against suffrage turned their attention to supporting the war effort.

When the federal amendment passed Congress in 1919, and was sent to the states for ratification, the grassroots movement in Princeton resumed, but not with the same fervor it had during the 1915 referendum fight. The community was still deeply divided on suffrage — in the State Legislature’s February 9, 1920 ratification vote, Mercer County’s State Assembly delegation split its vote.

Photo Caption: During World War I, women in New Jersey supported the war effort by providing labor in place of drafted men, such as on farms through the Women’s Land Army. The Princeton Farm Unit offered “women farm hands” to local farmers. Many suffragists hoped these, among other wartime contributions, would prove women worthy of the vote.

Women Come Together to Vote

Despite their lack of agreement on suffrage in Princeton, suffrage advocates and opponents united almost immediately after the amendment passed to ensure that women had the information they needed to vote responsibly.

On September 23, 1920, less than a month after the amendment’s certification, 400 Princeton women — more than had ever been directly involved in the movements for or against suffrage — assembled to hear a talk about the “duties and privileges of citizenship and the methods of voting.” Claire Kulp Oliphant, one of New Jersey’s most vocal anti-suffragists and author of the column series quoted below, delivered the talk. She spoke at the invitation of Georganna Gibbs Browne, one of Princeton’s strongest pro-suffrage advocates and the wife of the Borough Mayor. The event’s planning committee consisted of a combination of Princeton’s pro- and anti-suffrage women.

Now that women had the right to vote, these former rivals agreed that women needed to take it seriously.

A Lasting Impact

Though women of this period in Princeton never came to a consensus, the suffrage movement had a profound impact on women and women’s groups in the town. Organizing for and against suffrage taught women how to independently administrate organizations, canvass, and work with other women for common cause.

In Princeton, these women were instrumental in growing women’s clubs, such as the Present Day Club. The leadership of the Present Day Club drew from Princeton’s suffragist and anti-suffragist luminaries alike, including Catherine Warren, Frances Folsom Cleveland Preston, and Georgeanna Gibbs Browne.

Agnes Miller, a Princeton suffragist and town librarian, and Frances Folsom Cleveland Preston both became involved in a growing anti-war movement among suffrage-associated women for an international body for world peace.

Catherine Warren initiated efforts to establish a state college for women, a matter on which suffragists frequently noted New Jersey was woefully behind. This led to the 1918 establishment of Douglass College at Rutgers University.

Many black women who had been involved in the suffrage movement used their organizing and advocacy skills to focus on the crisis of lynching in the American South. Nationally, journalist Ida B. Wells Barnett made this her life’s work. In Princeton, suffragist Bessie Brown Mention took up this cause.